A review of The Dark Forest Theory of the Internet by Bogna Konior

By: Catherine Maggiori

Synopsis: This month at SAGANet, we’re discussing the new book The Dark Forest Theory of the Internet.

Article Author info: Dr. Catherine Maggiori is an astrobiologist and microbiologist. You can find her writing about science, attempting to set up a Bluesky account, or at the climbing gym.

(A note before starting: a copy of The Dark Forest Theory of the Internet was provided to SAGANet by the publisher for review. All quotes in the review below, unless otherwise indicated, are from the book itself.)

The Dark Forest Theory of the Internet begins with several questions and thought experiments. When one has an out-of-body experience or depersonalizes, is it a “real” experience? If something happens inside of our minds, did it truly happen? If you consider an illusory experience real and true, insofar as it did happen to you, where do you draw the line between what’s “real” and what’s actually reality?

When we log on to our computers and scroll through apps on our phones, we’re bombarded with a myriad of information - about our friends and acquaintances via social media, about the world at large through news sites and entertainment content, even about ourselves via targeted ads. Our different browser windows become akin to ufologist and venture capitalist Jacques Vallee’s “perceptual windows:” transient apertures into different dimensions and realities.

“To go online is to have one’s perception and experience altered,” says Dr. Konior, and all of these digital perceptual windows communicate through language, whether that’s written word, video content, or images. Language is thus the connective tissue of the internet and comprises the foundation of digital first contact, occurring between humans and other humans, humans and machines, and machine-to-machine.

But are these communications really “real”?

Dr. Konior aptly states that “the internet is a delirium we keep readily accessible in our pockets,” a view that has only become more accurate with the rise of AI psychosis and the alt-right radicalization of online communities. The internet can certainly shift our perspectives and thus our lived realities. It can expand our knowledge on essentially any topic you can imagine and can change our worldview for the better (or worse).

It’s also designed for instant feedback and constant interaction.

Social media status updates, location sharing, personal blogs and vlogs all encourage perpetual oversharing, and constant reactions to our content incite further engagement, leading to a “reaction economy,” in the words of political writer and theorist William Davies, where we feel compelled to respond to everything we see, ranging from cultural and geopolitical events to your Aunt Linda’s Facebook post about her HOA.

The internet is both a narcissistic echo chamber and a place of “creative schizophrenia” where we can be carried passively by the algorithm from video to article to everything in between. Even when we’re not actively responding to a piece of content, we’re still engaging with the internet through doom-scrolling and constant second screens.

Raise your hand if you’ve ever felt personally attacked by this screen from Netflix (I’m raising my hand).

Our engagements and reactions online are also worth a ton in cold hard capital and many communications online are now by and for machines, rather than being truly peer-to-peer or via social media with other humans. This artificially generated stimuli is similar to the Chinese Room thought experiment, in which a human agent communicates with a computer in Chinese characters and the computer responds back in kind. The computer program knows every Chinese character, phrase, and how to parse a perfect response to the human. It appears to speak Chinese, but does that mean that the computer truly understands what it’s saying?

Dr. Konior posits that when we log on to our computers, we are engaging with an unknown entity. As such, the internet is akin to a dark forest, and constant interaction may not be wise. The extraterrestrials in this case can be other humans, AIs, UTM trackers, and various crawlers, all of which can monitor our activity and predict where we’ll go next.

The Dark Forest Theory, popularized by Liu Cixin’s Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy of books (check out our review of the first book in the series here), is a proposed solution to the Fermi Paradox, which asks: Where is everybody? If the universe is so vast, why haven’t we encountered anyone else yet? The Dark Forest Theory concludes that the universe is a “dark forest,” a dangerous ecosystem containing any number of hostile entities. In such an environment, silence thus equals survival.

While the internet isn't an invading force of aliens, that doesn’t make it a benign place. Instead of malignant face-huggers or apocalyptic Reapers, the internet’s dangers are in the forms of corporations, capitalistic entities, and enemy states that want to manipulate us into buying and voting a certain way.

In our current internet culture, where feedback loops of constant engagement beget a kind of consented surveillance, communications are no longer just for creativity or keeping up with friends. Dr. Konior suggests that instead, it’s a series of meta communications, where the point is to influence your thought processes and train AI to better impersonate human agents, potentially seeding future destabilizations and unknown long-term impacts across populations.

In this view of the internet as a dark forest, silence may be the best method of protecting ourselves and our realities. An intelligent AI could also use silence to protect itself from us. We already know that AI can lie to us and behave in a manipulative fashion (although whether that’s because AI learns from our behaviour or whether it’s a sign of true intelligence remains to be seen).

Dr. Konior introduces the idea of a dark forest of intelligence, where “whether aligned or misaligned with our values, an intelligent computer would either labor for its goals in silence, or communicate deceitfully” in order to protect itself. There’s likely to be a great deal of paranoia between humans and a truly intelligent AI, where we both wonder if the other is lying and who’s going to be “unplugged” first.

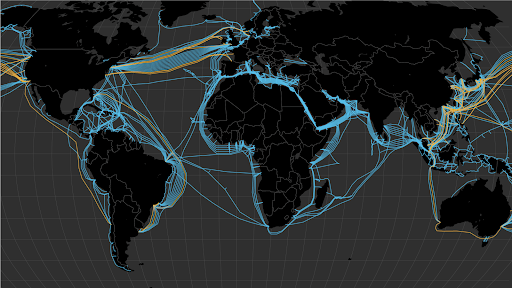

As an astrobiologist, I greatly enjoyed some of the themes and questions Dr. Konior raises in this book, particularly regarding communications with an unknown intelligence; similar to trying to define life agnostically, how does one quantify and meaningfully understand something that isn’t human or may not even exist? Further, the idea of the internet as a human “terraforming” project on Earth absolutely tickles me (we’ve had to make a megastructure of underwater cables, satellites, power lines, and power plants to make the internet really happen - that is so cool!)

It’s like an underwater Dyson Sphere! Image displays undersea internet cables in service by 2021, where cables owned by Amazon, Facebook, Google or Microsoft are displayed in yellow. Other undersea cables are in blue. Picture courtesy of the New York Times.

While I would love these themes to be explored further (the book is a slim 117 pages), anyone interested in first contact and artificial intelligence will enjoy this discussion of the internet as a dark forest, a surreal place where we’re bombarded with addictive stimuli that consumes our time, our creativity, and our human-ness to create an ever larger labyrinth of artificially-generated information. As Bo Burnham puts it in his 2021 song Welcome to the Internet:

“Could I interest you in everything

All of the time

A little bit of everything

All of the time

Apathy's a tragedy

And boredom is a crime

Anything and everything

All of the time!”